All Saints, Ramsholt

Read’s Roy Tricker’s church history – a summary follows

Background and to read Stephen Hart’s expert analysis

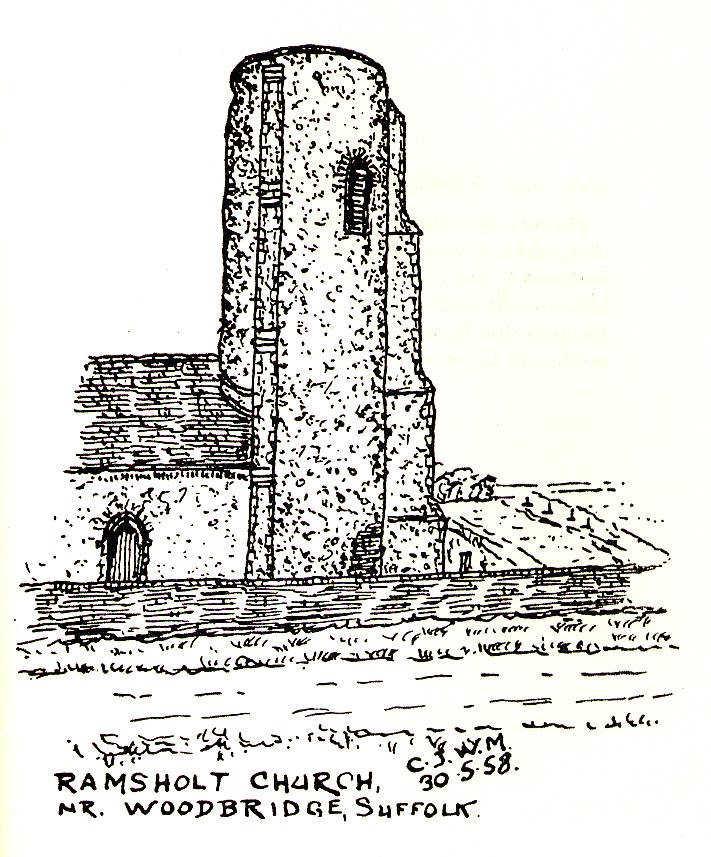

An isolated church at the end of a lane but close to the Deben estuary. There was probably a church here in Saxon times and an earlier tower – with a Norman arch was attached to this earlier church.

The current tower is built of Septaria (light to medium- brown limestone of coarse texture which outcrops in this area), flint and medieval brick. Stephen Hart argues that this tower was built in late C13 or early C14 together with its three buttresses as tower and buttresses have a similar mix of building materials, perhaps suggesting a problem with an earlier tower. Entrance is through a C19 porch. C15 font. Box pews and two-decker pulpit installed in mid C19. Jack Sterry describes Ramsholt in his 2010 book Round Tower Churches in Mid Norfolk, North Norfolk and Suffolk.

Roy Tricker’s church guide

By Roy Tricker, who wrote an informative guide to the church. The following summary is heavily-drawn from his guide.

The population of the parish, which it serves, is now one of the smallest in Suffolk. It is home to about 32 people having decreased from 152 in 1801, 186 in 1861 and 132 in 1921. The parish’s area is far from tiny, 2017 acres, of which 1,800 are land and the rest are water and foreshore – much of the southern part is marshland.

How old is the church?

The 1000s – Although the Domesday Survey (1086) does not mention a church at Ramsholt, it does not mean that one did not exist. The Survey describes what people owned – and was not a list of its buildings.

The simple early Norman tower arch (and therefore almost certainly also the core of the nave) dates from c1080 to 1100.

C 1270 to 1310 – The chancel was either re-built or re-ordered at this time when it received new windows (with simple ‘Y’ and intersecting tracery) and a priest’s doorway.

C 1400 to 1700 Although many Suffolk churches were transformed during the 15th century, All Saints was largely untouched. In the late 1400s, the chancel received its elegant three-light “Perpendicular” north window whilst the font bowl and the nave’s south-east window date from c1400. Tiny fragments of medieval glass remain near the very top of this window.

C 1700 – 1857 – the 1700s saw much neglect and decay in many of our church buildings – a case in point at All Saints. In 1706, the Archdeacon instructed churchwarden John Pretyman that “troughs and pipes to be put up, and a new burial-cloth to be provided.” Later, he ordered new cloths for the Communion Table, pulpit and reading desk to be bought.

A rough sketch of the church in c1726 which David Elisha Davy later reproduced, shows that the tower was crowned by a tiled conical cap. In 1747, it is recorded that “the top of the steeple was blown down and many other tiles from the church and chancel.”

Isaac Johnson’s sketch (drawn c1795 to 1818) shows it without its cap and another colour-washed picture (probably by him) shows in more detail the terrible state of the building with saplings growing out of the tower walls, its summit rugged and a gaping hole in the nave roof.

The crowing glory of the exterior is Ramsholt’s lofty (c 56 feet) and distinctive tower, which in its commanding position, is visible for miles from across the Deben. It is one of 181 round towers in England, of which all except 13 are in Norfolk and Suffolk. The tower is strengthened for its full height by three study buttresses, giving the impression that the tower is oval. Actually careful measurements have shown that it is – but only just – the difference between its north-south east-west diameters being about seven inches. Doubtless several other round tower are just as “oval” – or more so.

The other (and much shorter buttressed round tower, at Beyton, near Bury St Edmunds), has two buttresses. Opinions vary as to the date of this rather eccentric tower. The latest thinking (backed by very sound reasoning) dates its construction to the late 1200s, possibly replacing an earlier tower.

Unusually because of the positions of the buttresses, there are three belfry windows (single early English ‘lancets.’ as is the lower window,) two of which face north-west and south-west. Its wall is punctuated by small square put-log holes, framed with medieval bricks (and now filled in), into which the builders of the tower placed their wooden scaffold poles. On the east face, above its present roof, are the ridge marks of a much earlier and (probably thatched) roof.

The north and south doorways of the nave date from c1300, although the nave wall may well be over 200 years older.

The curious little (almost certainly brick) windows – two double windows high in the north wall and a triple window nearer the porch – were probably added during the 1500s or 1600s to increase the light provided by the nave’s beautiful two-light south-east windows, which was fashioned around 1450.

The chancel has kept the two-light south windows and doorways with which it was provided by the Canons around 1300, with similar interesting tracery in the three-light east windows. The triple window on its north side, of the plaster-covered Tudor brick, was probably added around 1500.

The tower contains the church’s single bell, weighing 5cwt, which has been ringing out across Ramsholt and the river since 1679, when it was cast at John Darbie’s bell-foundry, which was near the docks in Ipswich.

Ramsholt clergy

Ramsholt was one of several parishes whose parish priest, after the Reformation, was not a Rector or Vicar, but was legally called a “Perpetual Curate.” Many parishes, once in the care of Augustinian monasteries (as Ramsholt was) were perpetual curacies until the legal title was abolished in 1968.

After the monasteries were dissolved in the 1530s, their possession were either given to sold to “Lay Impropriators” who were responsible for nominating a parish priest to the Bishop and for providing a set salary for him (the value of which tended to decrease over the year), which means that they were often served by a neighbouring incumbent. Ramsholt, being regarded as a poor parish, received a grant of £70 pa from Queen’s Anne’s Bounty to enhance its capital.

A perpetual curate was directly licensed to the Bishop and did not need to be formally Instituted or Inducted to the parish; he could only be removed from office by him and not by a patron or Impropriator.